Letter from the Chair and Executive Sponsor

Like so many organizations, the Texas Collaborative for Healthy Mothers and Babies has been engaged in a conversation about how to stay true to our commitments while adapting to the realities of a health care system that has had to shift priorities in ways we couldn’t have anticipated even two months ago.

Dear Friends and Colleagues,

Our thoughts are with you and your families as you do your best to weather the COVID-19 crisis.

Like so many organizations, the Texas Collaborative for Healthy Mothers and Babies has been engaged in a conversation about how to stay true to our commitments while adapting to the realities of a health care system that has had to shift priorities in ways we couldn’t have anticipated even two months ago.

In light of this new reality, we will continue with our current quality improvement programs, but will shift deadlines, expectations, and metrics as needed. The leadership and committees will continue to meet, but will do so remotely and in some cases less often. We will continue to communicate about our initiatives through our newsletter and on social media, but will do so less frequently than before. We will also post perinatal-specific resources on dealing with COVID-19 on our website.

Paid staff at UT System will continue to dedicate their time to TCHMB as before, but much of the clinical leadership on the committees and in the hospitals and clinics may not be able to dedicate as much time as they were prior. And we will all continue to adapt as the situation changes.

Stay safe, and please reach out with questions and suggestions.

Sincerely,

Michael E. Speer, MD

Chair, Texas Collaborative for Healthy Mothers and Babies

David Lakey, MD

Vice Chancellor for Health Affairs and Chief Medical Officer, The University of Texas System

TCHMB Wins 2nd Place in National Improvement Video Challenge

The TCHMB-produced video, “MEWS: A Simple Alogorithm for Reducing Maternal Mortality and Morbidity, has been awarded second place in the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care’s National Improvement Video Challenge.

The TCHMB-produced video, “MEWS: A Simple Alogorithm for Reducing Maternal Mortality and Morbidity, has been awarded second place in the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care’s National Improvement Video Challenge.

Diabetes Screening and Treatment Available for Healthy Texas Women Clients

To learn more about which medications are covered, healthcare providers can access the HTW specific formulary at txvendordrug.com/resources/downloads.

Healthy Texas Women is a program dedicated to offering women’s health and family planning at no cost to eligible women in Texas. Since July 1, 2016, the HTW program has provided coverage for screening and treatment of hypertension, diabetes and high cholesterol.

In the most recent Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force and Department of State Health Services Joint Biennial Report, chronic health diseases such as pre-pregnancy obesity, diabetes and hypertension were all associated with an increased risk for maternal death. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that almost 25 percent of people with diabetes and 20 percent of people with hypertension are undiagnosed.

By increasing access to vital health services and treating underlying medical conditions, women’s health and pregnancy related outcomes can improve in Texas.

Several commonly prescribed medications used to treat these conditions are available on the current HTW drug formulary. Clients approved for HTW can get these medications at any Medicaid participating pharmacy with their program identification card.

To learn more about which medications are covered, healthcare providers can access the HTW specific formulary at txvendordrug.com/resources/downloads. Participating HTW providers can access information regarding policies, billing guidelines and toolkits at healthytexaswomen.org/provider-resources.

An Alliance Is Born: Jeanne Mahoney on the Birth and Growth of the Alliance for Innovation in Maternal Health Care (AIM)

We speak to Jeanne Mahoney, Director of the National AIM initiative, about the origins of AIM, the reasons for the rise in maternal mortality, and the development and dissemination of AIM’s bundles.

For most of the past century, the trend in maternal mortality in the US was a good one. Fewer women were dying in connection with their pregnancies. The trend was so good in fact, that many states and cities retired their maternal mortality review committees. They didn’t seem necessary anymore.

Then something changed. Beginning in the mid-2000s, the numbers started going in the wrong direction. More mothers were dying.

Over the past decade, a new infrastructure has emerged to address that critical and tragic trend. At the center of it is the Alliance for Innovation in Maternal Health Care (AIM), which Jeanne Mahoney directs through her work for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). 28 states (including Texas) are now implementing AIM safety bundles, with the remaining 22 states either intending to get involved or exploring involvement.

We spoke to Mahoney, who was an invited speaker and panelist at the 2019 TCHMB Summit, about the origins of AIM, the reasons for the rise in maternal mortality, and the development and dissemination of AIM’s bundles.

Mahoney came to ACOG in 2002 from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, where she was involved in coordinating risk reduction programs for women of reproductive age.

---

TCHMB: What’s the story behind AIM? I was looking at the maps you showed at the conference, of the recent and rapid spread of AIM states, and it’s all very recent, isn’t it?

Jeanne Mahoney: Yes and no. In a way it starts in 1992, when a group of people interested in maternal mortality began getting together at the annual ACOG meeting. It was OB/GYNs, public health people, anesthesiologists, all sorts of people who were engaged with women’s health. At the beginning the group wasn’t meeting with a sense of alarm. The numbers had been going down for decades, and the assumption was that they would continue to do so. Then around 2008, we started seeing these numbers rising, and that changed the tenor of the discussion.

Elliott Main had been tracking the numbers in California and seeing the same kind of rise. It became very clear that it was a real problem, not just a statistical fluctuation.

We pulled together a group in 2012 to do a real deep dive into the data and to begin to formulate a national response. What we saw was that there wasn’t just one cause of the rise in maternal mortality. There were many overlapping causes, as well as a great deal that we didn’t yet understand. What we saw clearly, though, were two major cause that were remediable, maternal hemorrhage and hypertension. These were issues about care that we could do something about there and then.

At the national ACOG meeting that year we had a big meeting of about 150-180 people. We came to a consensus that we would begin to develop and deploy maternal safety bundles. We called the group the National Partnership for Maternal Safety. It was not really a card-carrying organization, but it helped formalize the structure. Out of that came The Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM), which is staffed by us here at ACOG but is a true alliance. There are 30 different partners across multiple sectors that work with us on every aspect of AIM.

Why did the maternal mortality numbers start going up after so many years of progress? I realize it’s complex, and there are really long answers to that question, but what’s the short version?

For the two issues that we started out with, maternal hemorrhage and hypertension, I can give you some relatively straightforward answers that explain a least a substantial part of the cause.

With maternal hemorrhage we call it “too much too soon too little too late.” We are not waiting for women to have their babies. As a culture we started doing more inductions, more c-sections. We kept pushing the envelope. We have been inducing labor in too many women who don’t have medical reasons for induction, and if the babies fail to arrive on schedule, during an induction, we give the mother more and more oxytocin, and that can be dangerous.

Oxytocin causes the uterus to contract, and the uterus is a muscle like any other muscle. If you force it to contract over and over, it gets tired. After birth it is supposed to contract hard, but too much oxytocin can increase the risk of it failing to contract while the uterine blood vessels continue to pump blood—up to 1/8th of a woman’s total blood volume per minute. The risk increases the longer it takes us to recognize the bleeding.

There is a different hypertension story. Blood pressure has been going up overall in pregnant and postpartum women. We’re not entirely sure why, but that increase has intersected with a slowness, on the part of providers, to implement best practices in how to manage the blood pressure of pregnant and postpartum women.

The walls of the blood vessels of women who are pregnant and early postpartum are very thin, and so the vessels can leak at lower blood pressures than in other people. For a long time that wasn’t the training we were getting. We were taught that the danger zone for pregnant and postpartum women was the same as in other people. We know now that the danger threshold is lower than for the general public. The systolic number, the top number, should never go above 160. Normally we don’t start to treat blood pressures until that systolic number is over 180. By that point, a pregnant or early postpartum woman is much more susceptible to having a stroke and dying.

We have to retrain our providers on every level to be able to understand the hemodynamics of pregnancy and postpartum, so we aren’t sending women home from the hospital early, and we are responsive when they are exhibiting warning signs.

Another big part of the story is women dying from drugs and particularly opioids. Those are mostly killing women post-partum. In Texas right now, for instance, that is accounting for about 50 percent of maternal mortality. One of the ways this is happening is that during pregnancy, many women get some kind of medication assisted treatment for opioids, but then Medicaid runs out 42 days postpartum. Soon after, they go straight to street drugs to treat their disease of addiction, and they overdose and die far more frequently than women using opioids who have not been pregnant.

So how did you get from that big meeting in 2012 to the actual development and deployment of safety bundles? To the official launch of AIM?

We decided our bundles were going to be evidence-based best practices, and that we would pull together a team of experts to develop them. It was multi-disciplinary work-groups of 10-15 people who had to come to consensus. The groups included nurses, doctors, the head of the American Blood Bank Association, someone from the national obstetric anesthesiologists association, and others.

It was hard to come to consensus, having that many different organizational folks sitting around the table. Our hemorrhage bundle, for instance, took us almost two years, because we needed to learn how to work together. At the same time, that process was immensely valuable, both on its own terms and because when we finally did achieve consensus, we already had those organizations on board, affirming this work.

The key with the bundles is that they are very specific in certain ways, and very open in others, so that the hospitals have a lot of flexibility in how they implement them. These are the practices that you need to do, and now you figure out how to do it. If we talk about a medication, for instance, we don’t put dosages in, or instruct providers how to give them. That makes it a lot easier on the implementation end, and so our bundles endure. The hemorrhage bundle, which we developed in 2013-2014, hasn’t changed at all. We review it every 18 months or so, to see if it still applies, and although we have added some references, the itself bundle remains the same.

How did you get the bundles out into the world? It is one thing to have a good set of tools. It’s another thing to get people to use them, and to find the resources to support that.

We began working on the bundles in 2013. In 2014 we applied for and received a grant from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau at HRSA for what we were now calling the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health, or AIM. We came out with the hemorrhage and hypertension bundles around then, and then we kept going. We now have 10 bundles, including bundles on venous thromboembolism prevention, postpartum care, reduction of racial disparities, and opioid use disorder.

In terms of getting buy-in more broadly, it helped that from the outset we had support from the broad coalition of organizations involved in the development of the bundles. They were partners in the grant application and gave us credibility as well as avenues for dissemination and outreach. We also worked out a really unique deal with the major disciplinary journals for the simultaneous publication of the commentaries that add implementation support to each bundle. These commentaries flesh out the bundles with definitions, references, discussion of issues that need more discussion, and so on. Whenever we release a bundle the commentary is published in three to five separate peer reviewed journals simultaneously.

Even with all that support, though, at first we were hard pressed to find states to participate. No one understood what we were doing, and we had to sell them on it. Over time, as we’ve established ourselves, and demonstrated the efficacy of the bundles, getting buy-in has become easier.

What is the efficacy?

We are seeing in the hospital outcome data that the states that are doing any bundle at all have reduced their severe maternal morbidity rates 8-25% across the board. A lot of that improvement, we believe, is the result of just pulling the teams together and working on an issue together. It is changing the way people are thinking. They are working together, and that produces good outcomes.

Do the bundles make the work of providers harder? Is it more work?

Yes and no. The bundles themselves are best practices we should be doing anyway. They’re substituting more effective practices for less effective practices. The data part is a little trickier, because in many cases it is adding several process and structure measures that need to be entered into a data system. Doing rapid cycle data driven quality improvement provides the basis for action and is highly valued.

You mentioned the racial disparities bundle. That feels like a very different challenge to tackle than the other bundles. It’s one thing to say that you should always have a hemorrhage cart nearby in situations x and y. It’s very different to tell providers to be less racially disparate, when we don’t even know most of the causes of racial disparities.

It is very tricky, and also very important. We see these incredible disparities in morbidity and mortality. But also variation in the degree of disparity, which suggests that there is a lot of room for improvement. New York City, for instance, has a twelve-fold difference between black and women dying. Illinois has a six-fold difference. Across the country we are seeing a 3 to 4-fold higher rate of black maternal mortality.

This is not just about black women coming in with higher risk factors. One thing we are finding is that there are communication issues. We are not listening to some women as well as we are to others. So somebody says, “I am having pain,” and instead of exploring the possible causes of that pain, the response is, “You’ve just had a baby, of course you have pain.” That happens more to black women than white women. We need to find ways not just to close the gap but to improve communication with all women.

Right now we have a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to try to quantify those voices of women, to develop measures that we can track and give back to providers to let them know how they’re doing and how they can improve.

That sounds fascinating, but hard. How would you do that? How do you quantify that kind of subtle communication?

It’s complicated. The grant with RWJ involves studying interactions and identifying key words and phrases that can signal, for instance, that communication is failing. And not just words, nonverbal communication as well. The goal will be to train medical providers to be alert for those key words and gestures that signal that they need to listen more closely. And not just the physicians, the other providers as well, so that there are multiple people listening to and looking out for women.

It is not going to be easy work, but we have hospitals who want to be part of the pilots, which is an indication of the interest in addressing the issue.

One thing I noticed at our conference this year was how many nurses were there. That surprised me, but it probably shouldn’t have. Is that true nationally?

Yes. In every meeting we have for AIM, there are more nurses than docs. Some of that is a result of who the hospitals are choosing as their representatives. They’re more likely to send nurses. But it’s also because nurses really like this work, because it empowers them to provide the best care for their patients. They’re not having to negotiate conflicting instructions from different doctors, and in many cases, it provides them the means to intercede if the care is not being provided according to the bundle.

What’s on the horizon for AIM?

We’re working with more and more states, like Texas, on implementing bundles. We have projects that are focusing on improving care, and customizing bundles, for rural settings. We are rural-izing them, as one of our partners in North Dakota said. We are doing work internationally. Did a project in Malawi, for instance, in which were able to reduce maternal mortality due to hemorrhage in three hospitals by 83%.

We’ll keep working to improve the health of mothers.

Three Things: Dr. Ann Borders on What Makes or Breaks a Perinatal Quality Collaborative

We spoke to Dr. Ann Borders, Executive Director of the Illinois Perinatal Quality Collaborative (ILPQC), about how state perinatal quality collaboratives can make a real difference in the lives of mothers and babies.

When Dr. Ann Borders was tapped to help launch the Illinois Perinatal Quality Collaborative (ILPQC), her first move was to ask for help. Other states had successfully launched and developed PQCs. Illinois’ best bet for achieving its own success, she knew, was to learn from them.

“We asked them, ‘If you were starting a new PQC what would you do?’” said Borders, Executive Director and Obstetric Lead for the ILPQC. “Then we went home and tried to imitate that.”

They succeeded. In the five or so years since, Illinois has emerged as one of those states worth imitating in its own right, with over 100 birthing hospitals participating in its initiatives and an impressive record of improving outcomes for mothers and babies. Borders herself has emerged as a national expert on creating, growing, and sustaining a PQC, and now serves on the National Network of Perinatal Quality Collaboratives Executive Committee.

We spoke to Borders after her keynote speech at the 2019 Texas Collaborative for Healthy Mothers & Babies Summit.

—-

Dr. Ann Borders at the 2019 Texas Collaborative for Healthy Mothers and Babies Annual Summit

TCHMB News: When you first were launching the Illinois Perinatal Quality Collaborative (ILPQC), what did you do to maximize the chances of success?

Dr. Ann Borders: We started with that premise that we needed to learn from successful collaboratives, in states like Ohio, California, Florida, and North Carolina. We very specifically sought their input.

I remember we got a team together from Illinois to attend the annual meeting of the Florida PQC. We flew down there, and set up meetings with the Florida leadership, which was led by Bill Sappenfield, as well as with Jay Iams from Ohio, Elliott Main and Jeff Gould from California, and Marty McCaffery from North Carolina.

We asked them: How did you put a structure together? How did you create a data system? How do you interact with your teams? What are pitfalls to avoid? What are the key steps to be successful with stakeholders? We went home and tried to imitate their recommendations.

Illinois is now seen as one of those PQCs that knows how to make it work. You’re brought in (to Texas, for example) to help newer PQC launch and grow. From your perspective, what’s the secret?

From our experience, the collaboratives that make it work provide value to the hospital teams. I’d break that down into three strategies that are key to this work:

Provide opportunities for collaborative learning, getting teams together to share and learn from each other, whether that’s in person or through calls and webinars.

Have a rapid response data system that hospitals can really utilize to compare data across time and across participating hospitals to effectively drive QI.

Provide quality improvement support, primarily with QI coaching calls and follow up. Teams may also need site visits with key player meeting when appropriate or small group discussion calls to link up higher performing hospitals with hospital teams still struggling with a particular QI topic. The goal is to help every hospital succeed.

What about the ones that aren’t as effective? What are they doing wrong, or failing to do?

Every state is different in terms of the stakeholders, the funding, and the available infrastructure, so it is never one size fits all. We do think, however, that there are some strategies that may help teams achieve success more efficiently and hopefully more effectively. We also believe that every PQC has something to learn from every other PQC, no matter how long they have been at this work. Collaborative learning across PQCs is just as important as collaborative learning across hospitals in order to achieve success.

In our experience, we have found it important to use a quality improvement model, have access to rapid response data, and have an infrastructure that provides regular communication with hospital teams and opportunities for collaborative learning. Collaboratives seem to be more successful when they focus on quality improvement strategies to help their hospital teams be successful. Also successful collaborative teams focus on one or maybe two initiatives at a time. They don’t try to take on too much. They have clear aims and only collect data that helps hospitals drive change and show progress towards improvement. They stay focused on helping teams implement clear, measurable system changes and culture changes at primarily the hospital level (some collaboratives have successfully added outpatient settings, though it can be more of a challenge).

I think some collaboratives may fall into the trap of taking on too much when getting started, and this can be a hard way to start. It can be hard not to do this when stakeholders are pushing collaboratives to be responsive across a number of areas, but teams can feel overwhelmed when asked to do too much and it is hard to show effective improvement. This can be frustrating for everyone. It should be clear what the strategies are for improvement and what the aims are for demonstrating success. In our experience, staying focused is important for PQCs to be successful and for helping hospitals succeed.

As the PQC movement has developed, there have been some collaboratives that started with more of a public health model: needs assessment, project implementation with education and resources, and then evaluation with vital record data or other population health data. That is a model that can work well in many public health settings, but it does not seem to support rapid-cycle quality improvement through implementation of systems and culture change in the same way as the strategies that we now see most PQCs embracing.

From our experience in Illinois, and in collaborating with other state PQCs, it is hard for hospitals to wait six months or a year for data on efficacy. It is hard to be able to successfully use that data to drive quality improvement. Teams that have access to rapid response data with easy to use reports can most easily use that data for quality improvement. Also many hospital teams need QI support, because hospital teams don’t all have the same experience and infrastructure to support quality improvement. Also we have found that hospital teams benefit if they are able to learn in real time from other hospitals.

Tell me more about what you mean by rapid response data. How do you set up the kind of system that works?

A challenge for every developing PQC is how to manage data. Figuring out a data system that can help hospital teams drive QI is one of the early key steps in PQC development. From our experience, ideally PQC’s have a system that can provide rapid feedback and that is managed outside of the vital records or state data system. In that scenario participating hospitals feel that the QI data they are collecting is their data for their data reports, and it reduces concerns regarding data being used in more of a regulatory fashion. PQCs use all different sorts of data systems and data sources depending on resources available and on how best to balance data burden for each initiative. Some vital records data, particularly when it can be accessed with rapid turn-around, can be really helpful to PQCs for specific initiatives. From our perspective, having a PQC-managed data system has been helpful in developing hospital team buy-in with participation and data tracking. Providing rapid response data reports provides significant value for hospital teams and certainly helps teams use their data to drive rapid cycle quality improvement.

This goes back to what I was saying about the goal of providing value to the hospital teams. When the hospital teams meet every month, it helps to have simple data reports to review that track progress across time and provide comparisons to other participating hospitals. Ideally they can put the data reports up on the wall and say, ‘This is how we are doing.’ That is real value provided to teams, and it empowers them to make changes within their hospital.

Regardless of the system a PQC is using, we always try to remember that we are not collecting the data for a specific initiative with any reason other than to track the progress of the initiative and give data reports back to the hospitals to drive quality improvement. The best situation is when the hospitals in the collaborative feel ownership of the collaborative and the data system. That makes the teams feel safe being transparent. It also really enables collaboration and sharing between hospitals within the collaborative.

To give that kind of rapid response, do you need someone on staff creating a host of reports every month, or is it automated?

It is automated. That requires a lot of work and thought on the front end, working with a programmer to code a system where hospitals can input key data, through REDCap, and then instantaneously get back the report through a web-based portal.

To achieve that, we decide what reports we want, test them, get feedback, and iterate. That all happens during wave one, where we ask 25-30 hospitals to test the data form and test collecting the data. They give us a lot of feedback on what they think is the best data strategy before they start any QI activity. Is it readable? Is it easy to use? Are we collecting the right data and producing reports that are useful

The data has to be specific to each initiative. You are using the data to drive action for a specific initiative, which means collecting data only for the initiative in front of you, and feeding it back only on that front. If you’re collecting too much data, it ceases to be quality improvement. It becomes a burden, and if hospitals can’t see the benefit they won’t want to participate.

For hypertension, for instance, we tracked four key issues: time to treatment, percent of women who had preeclampsia education at discharge, percent of women who had early follow-up, and percent of cases with a nurse / provider debrief on time to treatment. Just those four things. We tried to make the reports very specific to drive the work.

The data system can be hard for folks, particularly because states have already put a lot of time and resources into systems for collecting vital records, and that typically is a very different system than what seems to be most helpful to support QI. There is a natural tendency to want to make use of the data collection system you already have, rather than invest more time and resources into developing a new system. That is completely understandable, particularly given constraints of budgets and staff resources. But from our experience, our rapid response data system has been really important to our teams and the collaboratives success.

“Collaborative learning” is something that is easy to say, but maybe not so easy to achieve. What does it look like to you, in the context of creating a successful PQC?

In the PQC context we try to be very pragmatic and genuinely collaborative. When we are meeting, whether in person or on calls and webinars, we are focused on what’s in front of us that month, and in the coming months, and on really learning from each other. What are the key strategies this month? How are we doing so far? Can we hear from another state, or from other teams within the state, on what is working and what isn’t? It is very different from having a webinar on how to treat pre-eclampsia, or listening to grand rounds, someone dispensing clinical wisdom. We talk a lot about QI strategies, think about data utilization, work on understanding what the task is in really specific ways and learning from others. It is also really helpful to hear about another team's successful strategies because it makes the challenge feel achievable.

That makes sense when you’re talking about people who are already on board, but how do you drive broader culture and system change? Hospitals are not always eager to change.

Absolutely. If you just put those other things in place, but you don’t convince nurses and providers and hospital administrators why, and how, they need to change their practice, then you are not going to get meaningful changes.

We work on a lot of fronts to support the hospital teams in effecting change within their organizations. The data is a part of that. Rapid response data is great for the teams implementing the initiatives, but it can also be really useful in helping them get buy-in from their hospital. It allows them to demonstrate improvements on the ground as well as the continuing gaps.

The QI support is essential. Some hospitals have a lot of experience implementing QI initiatives, but many don’t. For those hospitals we can help fill in the gaps.

We can also help by providing education and resources to the hospitals. In Illinois we have created a kind of speaker’s bureau, where we have volunteer clinicians who offer to give grand rounds at hospitals. They can come in and say, this is what everyone else is doing. These are the best practices. You should do this too.

We provide toolkits and resources, including some we’ve developed and others from other collaboratives and groups like ACOG and AIM. We’ll print them out and give them to teams. We’ll give them documents they can modify and add their own branding to, make it their own. We provide online training modules for nurses and physicians. Whatever they need to move the ball down the court, whether it is something we have developed, or something another team has done.

Ultimately, though, it can’t rest on us. You need nurse and physician champions to be the charismatic leaders, to convey the urgent sense that implementing this work will lead us to improved care which will lead to better outcomes. You need folks who can step up in the leadership roles and be the people who tell the story, who can conceptualize what we are trying to accomplish.

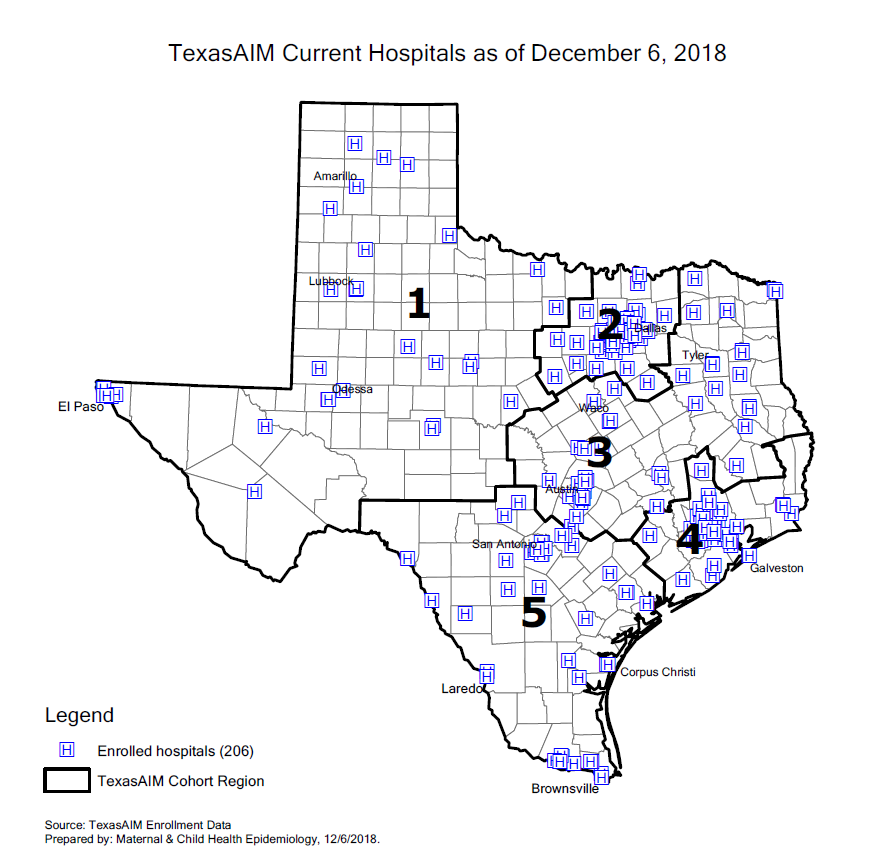

TexasAIM by the Numbers: 206 Hospitals and Counting

As of December 2018, 206 (92%) of Texas’ birthing hospitals are participating in TexasAIM. Of those, 167 are designated “TexasAIM Plus” hospitals, and the other 39 are “TexasAIM Basic” hospitals.

In our last issue, we spoke to Dr. Manda Hall, Associate Commissioner for Community Health Improvement at the Texas Department of State Health Services, about TexasAIM, a new initiative focused on reducing maternal mortality and morbidity in Texas. The initiative, which is being implemented by DSHS in partnership with the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM) and the Texas Hospital Association (THA), will help hospitals and clinics in Texas carry out maternal safety projects.

TexasAIM is launching with an Obstetric Hemorrhage Bundle. The initiative will then focus on the Obstetric Care for Women with Opioid Use Disorder Bundle and Severe Hypertension in Pregnancy Bundle.

As of December 2018, 206 birthing hospitals are participating in TexasAIM. That is 92% of all birthing hospitals in Texas.

As of December 2018, 206 (92%) of Texas’ birthing hospitals are participating in TexasAIM. Of those, 167 are designated “TexasAIM Plus” hospitals, and the other 39 are “TexasAIM Basic” hospitals.

Hospital Enrollment

TexasAIM Basic Hospitals: 39

TexasAIM Plus Hospitals: 167

Total TexasAIM Hospitals: 206

TexasAIM Hospital Cohorts

The AIM Plus hospitals are being divided into five cohorts, by geography, with 20-30 hospitals in each cohort. Each hospital will receive in-person learning sessions from DSHS. They will do an intake assessment, implement the QI bundles, and track and share process and outcome data over time. The hospitals in each cohort are also working together as part of learning collaboratives.

Cohort 1: 32 (16% of enrolled hospitals)

91% of participating hospitals are Plus

76% of hospitals in the region are in AIM

Cohort 2: 47 (23% of enrolled hospitals)

89% of participating hospitals are Plus

98% of hospitals in the region are in AIM

Cohort 3: 40 (20% of enrolled hospitals)

65% of participating hospitals are Plus

95% of hospitals in the region are in AIM

Cohort 4: 44 (21% of enrolled hospitals)

84% of participating hospitals are Plus

96% of hospitals in the region are in AIM

Cohort 5: 42 (20% of enrolled hospitals)

79% of participating hospitals are Plus

91% of hospitals in the region are in AIM

Geographic Area

Rural Hospitals: 74% of Rural Texas Hospitals are enrolled in TexasAIM (17 Basic, 28 Plus)

Urban Hospitals: 98% of Urban Texas Hospitals are enrolled in TexasAIM (21 Basic, 139 Plus)

AIM Data Center Portal

Registered Users in Portal: 402

Hospitals Active in Portal: 191 (93% of enrolled hospitals)

Hospitals with Structure Measures Entered: 176 (86% of enrolled hospitals)

Hospitals with Process Measures Entered: 160 (78% of enrolled hospitals)

TexasAIM: A Q&A with Dr. Manda Hall

We spoke to Dr. Manda Hall about the background to TexasAIM, maternal mortality and morbidity in Texas, and what TexasAIM will look like over the next few year

Manda Hall, M.D., is Associate Commissioner for Community Health Improvement at the Texas Department of State Health Services. She is also the state’s point person on the development and implementation of TexasAIM, a new initiative focused on reducing maternal mortality and morbidity in Texas.

We spoke to Dr. Hall, who is on the TCHMB executive committee, about the background to TexasAIM, maternal mortality and morbidity in Texas, and what TexasAIM will look like over the next few years.

Hall received her Medical Degree from Texas A&M University Health Science Center College of Medicine, and completed her residency and fellowship at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. She graduated as fellow from the Maternal and Child Health Leadership Institute at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and is a faculty member of the DSHS Preventative Medicine and Public Health Residency Program.

---

Before we talk about TexasAIM, specifically, I’d like to ask you about maternal mortality rates in Texas, and the controversy around that. What’s the pre-history to TexasAIM, in other words?

There has been a lot of discussion, nationally, about maternal mortality rates. Both because they are tragic, in themselves, and because they are important indicators of maternal health more broadly. We know that for every maternal death, there are 50-100 cases of severe maternal morbidity.

There has been a great deal of focus on this issue in Texas because there was a study published in 2016 that identified the rate of maternal mortality in Texas for 2012 as being exceptionally high. In May of this year, we published a new study of maternal deaths in Texas for that same year, using an enhanced method, that provided a more accurate estimate of the maternal mortality rate. The revised rate was 14.6 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, which is less than half of what had been previously published.

While our study showed the rate of maternal mortality to be far less than what it was, our findings are not reason to lose focus on the importance of reducing maternal mortality and morbidity. The rate is still too high, especially when we compare it to the Healthy People 2020 target of 11.4. When we look even closer at the data, we see that African-American women continue to bear the greatest risk for maternal mortality—more than twice as high as among hispanic and white women. We still have work to do.

Which brings us to TexasAIM. What is it?

It is a good example of what public health calls “data to action”. We are using the data and the knowledge gained and utilizing it to implement public health programming.

In this case, we are implementing a series of maternal safety bundles that were developed by the Alliance in Maternal Health, or AIM. It is a national program, overseen by the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG), that was developed with input and guidance from a broad group of partner organizations and experts.

These maternal safety bundles have been implemented in other states, and have led to a significant reduction in severe maternal morbidity, and in some cases, in mortality as well. We are now working to implement them here in Texas, and that, in a nutshell, is TexasAIM.

Before getting deeper into the details of TexasAIM, can you tell me what a “bundle” is, in this context?

A bundle isn’t comprised of a single item or guidance or intervention. Rather, it is a collection of resources aimed at achieving a specific goal. It includes items like checklists, best practices, and example protocols. You bring those together so they can be utilized by a team to improve outcomes. They’re designed not only to emphasize evidence-based interventions and strategies, but also to be flexible enough to be deployed differently in different contexts.

TexasAIM is focused on implementing three bundles: obstetric hemorrhage, obstetric care for women with opioid use disorder, and severe hypertension in pregnancy.

What does that mean in practice, for hospitals in Texas?

We now have more than 180 hospitals enrolled in the program, which represents more than two thirds of all the birthing hospitals in Texas, or approximately 82% of the births in our state.

Each hospital is enrolled in either AIM Basic or AIM Plus. Hospitals enrolled in AIM Basic have access to resources and technical assistance. They will report measures to the AIM portal, and have access to that data. They will form an improvement team, and will have the opportunity to transition to AIM Plus if or when it makes sense for them.

Texas is vast and varied, so one of the key elements of our strategy is to think regionally. The AIM Plus hospitals are being divided into five cohorts, by geography, with 20-30 hospitals in each cohort. Each hospital will receive in-person learning sessions, from DSHS. They will do an intake assessment, implement the bundles, and track and share process and outcome data over time, which will allow us and the hospitals to measure change. The cornerstone of all of this is the ongoing learning collaboratives among the hospitals in each cohort.

We recognize that hospitals are starting in different places. We have hospitals that have already implemented many of the elements of the bundles, while others aren’t as far along. The collaboratives will facilitate the hospitals learning from each other, sharing expertise and knowledge, and working through challenges.

Is it all voluntary?

Yes. Both levels of TexasAIM are voluntary programs for hospitals who are interested in participating. There is no penalty for not participating.

There is the opportunity, however, to use the implementation of these bundles to meet the requirements for neonatal and maternal levels of care designation, which will be required for Medicaid reimbursement beginning this fall for neonatal designation, and in 2020 for maternal designation.

To meet the requirements, hospitals must have a Quality Assessment and Performance Improvement process in place. It doesn’t have to be TexasAIM, but it can be.

So no stick, but a carrot.

Yes. More important, though, is the general recognition throughout the state that these are issues of extraordinary importance, and that this is a meaningful way to address them. The level of participation and collaboration is a testament to that. We have worked closely with the Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Taskforce, Texas Collaborative for Healthy Mothers and Babies, Texas Medical Association, Texas Nursing Association, ACOG, and the Texas Hospital Association. At our leadership summit on June 4th, which was the formal launch of TexasAIM, there were representatives from over 150 hospitals. We now have more than 180 hospitals enrolled. That is an exceptional level of participation for a state as big and diverse as Texas.

So what now?

As hospitals are enrolling, they are doing the intake assessments, to get a measure of where they are starting from. We are beginning with the bundle on obstetric hemorrhage. Then we’ll phase in the hypertension in pregnancy bundle. The opioid use disorder bundle is still in development at the national level, and we have been invited by the AIM program to participate with other states and experts on the final development of that bundle. We will implement that bundle as a pilot beginning this summer, with the goal of implementing this bundle statewide in spring to early summer of 2019.

How will you measure success?

By tracking the data over time, we hope to see marked reductions in maternal morbidity. It is possible we will see a decline in maternal mortality as well, but maternal deaths, although terribly tragic, are rare events, so it is harder to see statistically meaningful shifts in that rate over short periods of time.

Any final thoughts?

We need to ensure that the family voice is present in the work we were doing. At the TexasAIM summit, we were fortunate enough to have mothers and fathers present who shared what had happened to themselves or their loved one who had died from complications during pregnancy and delivery. Some even spoke directly to hospital representatives who were in the audience, asking for change, and it was really powerful and profound. This isn’t just about numbers and best practices. It’s about keeping women alive and healthy, and keeping families whole.

Q&A: Dr. George Saade

We talk to Dr. George Saade, chair of TCHMB, about his career in maternal and infant health, the work of the Collaborative, and more.

George Saade, MD, is a professor of obstetrics and gynecology and the director of the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Division at The University of Texas Medical Branch. He has served as the executive chair of the Texas Collaborative of Healthy Mothers and Babies since the collaborative’s beginning, and with more than 200 articles published in peer-reviewed medical journals, Dr. Saade is a recognized expert on preterm birth, preeclampsia, and the fetal origins of adult diseases. Late last year he talked with the TCHMB newsletter about how he began his career, the beginnings of the collaborative and what he's most excited about moving forward.

By Kaulie Lewis

Population Health Scholar

University of Texas System

Master's Student in Journalism

UT Austin Moody College of Communication

How did you become involved with maternal and perinatal medicine?

I like surgery, but I don't like only surgery, and I like medicine but I don't like only medicine, so this is a good field that combines both. It keeps me interested.

More importantly, though, is that so much is not well researched and not established in perinatology. When I was starting in this field, there was a lot of room for research, for developing new treatments and finding causes of diseases -- a lot more than in other fields where more people were working and doing research and things were advancing quite a lot.

Thirdly, I wanted a specialty where I could make a difference very early on. In perinatology, you’re working with two lives, young women and their babies. Whatever we can do in pregnancy will have long term benefits and implications compared to some specialty where you're treating people in the later stages in their lives.

Dr. George Saade, Professor and Director of the Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine at UTMB.

Why do you think that there hasn't been more work done before this?

I think overall if you take the history of medicine, women's healthcare was long relegated to the side. At the time when modern medicine and surgery were developing, obstetrics was thought of as just dealing with how to deliver the baby. It wasn't thought of as a scientific medical area. Women died during childbirth, but people thought that was inevitable. They didn't really think there was anything to do about it.

Then people started to understand the physiology of pregnancy, and began to get better at preventing deaths from hemorrhage or from sepsis and infection. Then we started seeing all these other complications. Now every pregnancy is seen as precious, not just for the woman and her life but for the whole family. There’s not an expectation that you need to have 10 or 12 kids so that maybe half of them will survive.

What are some exciting things that you're seeing in the field now?

I think there is more realization now of how significant an impact pregnancy has on long-term health for both the mother and the child. Some 20 years ago David Barker, who was an English epidemiologist, popularized the idea that what happens as the fetus develops impacts long-term health. There's an association between smaller size at birth and poorer health later in life. People call it the developmental origin of adult diseases.

So now, all of a sudden, pregnancy becomes an important window. Even if the pregnancy outcome is okay, the baby survives and the mother survives, we know that there is an association with long-term health. That’s also true for the mother, because now we know that the women who have pregnancy complications also tend to have cardiovascular and metabolic diseases 10, 15 or 20 years later.

That's where I'm spending a lot of my efforts, on what I call pregnancy as a window to future health. We know that if we make sure the pregnancy is going normally, and if we follow women who have pregnancy complications or babies that have small birth weight or are preterm, we can improve their health outcomes later in life and impact health care and health costs. When it comes to pregnancy, there is a return on investment multiple times over compared to what you invest in somebody who’s 60 or 70. Those are more short-term investments.

What projects are you working on right now? Anything coming up that you're excited about?

In the lab, we’re working on development and long term health, so we have some animal models of dietary restriction and how we can prevent long-term adverse outcomes in the offspring. We also have models of pregnancy abnormalities and we're looking at what can prevent the long-term cardiovascular and metabolic diseases in the mother. It turns out that oxytocin coming from breastfeeding and lactation may have a big benefit, so that's a good sign. Hopefully when we understand this more, we can prevent these long-term adverse outcomes.

On the clinical side, in the next few months we're going to start the national trial using tranexamic acid, which is a drug that prevents fibrinolysis. It improves clotting. We're going to try that to prevent postpartum hemorrhage after cesarean deliveries.

In addition to your research and your practice, you're also the chair of the Texas Collaborative for Healthy Mothers and Babies. How did you become involved in the collaborative?

I was involved in the precursor of the TCHMB. At the time it was called Healthy Texas Babies, and it was a collaboration put together by the state that included neonatologists, perinatologists and obstetricians. Each group of specialists picked a project to work on, and the leader of the obstetricians' group chose preventing non-medically indicated inductions and deliveries before 39 weeks, which was a hot topic at the time. I was brought in to advise and work with them because I had worked with the Society for Maternal and Fetal Medicine in developing guidelines for delivery before 39 weeks. We came up with some guidelines and policies, and the state adopted these indications so that providers had to certify that if they delivered somebody before 39 weeks, the mother had to have an indication that corresponded to what we listed. It was very successful. I think we really impacted the field.

So that's how I became part of Healthy Texas Babies. When the state decided to formalize this group and make it into a collaborative, I applied to be on the executive committee because I saw how impactful such a group can be. We still have some challenges, but it’s a young collaboration that’s moving in the right direction.

What are some of those challenges? What are some things that you are hoping to improve in the collaborative?

Connecting all the different stakeholders is the first step and the biggest challenge here because of how spread out Texas is. People say, “Well, state X or state Y did this project, did that,” but I can say from talking to other state collaboratives that they don't have the same challenges we have in Texas.

Take North Carolina. No patient in the state is further than 70 miles from a major medical center. We don’t have that in Texas. Here patients may have to travel 200 miles to reach a major medical center. That’s why so many deliveries in Texas occur in small, rural hospitals, and those hospitals often don’t have the infrastructure to collaborate on our projects. They’re doing a great job, but they have limited resources and may not be able to be a part of the projects that we want to do, whether it’s collecting data or instituting programs or implementing toolkits or bundles. If we push them too much, they may stop doing obstetrics altogether. Most of them are probably losing money on obstetrics already, so you can't just keep pushing them because otherwise they’ll have to close and then those patients will have nowhere else to go.

So in a sense it's a fine balance between what we want to do and what's feasible in Texas. That’s the biggest challenge that we have to overcome before we can do much more than what we are doing right now.

The other challenge is that Texas isn’t one of the states that often mandates things from the state government down to practitioners, so we're limited on what we can do. We can go to people and tell them that we're here to help, we're here to give them options for what they can do and how they can improve, but we can’t mandate what they have to do. If you combine that with the distances and the fact that rural hospitals are more common in Texas, you can see how it's going to be very hard to implement something that we think should be done.

All that being said, it’s remarkable how many hospitals TCHMB is working with.

I think the word is spreading. We're developing a very large collaborative and these things take time for everybody to get on the same page. I also think that our work with UT Health Northeast and Dr. Lakey’s team has improved our ability to reach out to hospitals. From the TCHMB newsletter, the Texas Health Journal, the work on organizing data and data analysis, all of that has tremendously increased our capacity to move things forward. Even though the collaborative was around before UT Health Northeast came on board, I think that partnership has made us a better collaborative.

"People say, 'Well, state X or state Y did this project, did that,' but I can say from talking to other state collaboratives that they don't have the same obstacles we have in Texas. "

What are you most excited about moving forward?

Collaborating with the perinatal advisory committee on the levels of neonatal care is going to be very important. I think the neonatal part of the collaborative is working really well because all the state’s NICUs have been connected for several years. They all function collaboratively. And now there is an official status for levels of neonatal care, so the NICUs have to be certified and they have to work together. The state is divided into regions and they have to work within those regions, and so that's something the collaborative can leverage and use to improve our communication and to improve our impact.

Next there’s going to be similar levels for maternal care and that’s huge, because this will be the first time that that’s happened. The NICU levels have been around for 20 or 30 years, but the maternal levels are new. So we need to seize this opportunity to work through that structure, to help educate and spread the message and the projects that we want to do. This is really the next step that’s going to propel us to the next level. I think we have some exciting years ahead of us.

Especially in this moment when maternal care in Texas has been getting a lot of attention because of our maternal mortality rates. Is that connected to why these maternal care levels are being implemented?

It's another chapter in the same story. About five years ago, I and some of my colleagues wrote a call to action. Why were we having these maternal mortalities? It was a national thing, not just for Texas.

We said then that neonatologists had developed these levels of NICU care in the ‘70s and they'd improved them in the ‘80s and ‘90s and now it’s a standard thing to have levels of neonatal care. Why weren’t we doing the same for maternal care? Then the Society for Maternal and Fetal Medicine and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists put a group together and came up with the recommendations for levels of maternal care.

I do believe that the levels of maternal care will improve pregnancy outcomes and decrease maternal mortality and, importantly, maternal morbidity. It may take some time to see the benefits, but I have been told by many colleagues that just having the discussion about this has improved the support they get.

Remembering James A. Cooley

James A. Cooley, a healthcare researcher and analyst in the Medical and Social Services division at the Health and Human Services Commission, died Nov. 11, 2017.

James A. Cooley, a healthcare researcher and analyst in the Medical and Social Services division at the Health and Human Services Commission, died Nov. 11, 2017. In his ten years at HHSC, he worked on several initiatives, including the Medicaid/CHIP super-utilizers program, but his work in improving the quality of health for Texans stretched beyond that. As a chief legislative staff member for the House Committee on Public Health and the Select Committee on State Health Care Expenditures, he worked on furthering health information technology, including helping to establish the Texas Health Services Authority.

In a post on the Texas Health and Human Services web site, Quality and Program Improvement Director Matthew Ferrara described Cooley as a sunny personality, good-natured and with formidable intellect and keen insight. Ferrara said Cooley’s contributions to healthcare and advancing health were numerous.

Conference: Obstetrical and Neonatal Care Coordination Related to Infectious Diseases in Pregnancy

The Texas Collaborative for Healthy Mothers and Babies (TCHMB) is facilitating a two-day conference on January 22 – 23, 2018 at the AT&T Conference Center in Austin, Texas. The conference is titled: “Obstetrical and Neonatal Care Coordination Related to Infectious Diseases in Pregnancy."

Date: January 22-23, 2018

Location: AT&T Conference Center in Austin, Texas

Cost: Free

Agenda: Download

Funder: Partially funded by the Texas Department of State Health Services

Hosts: Driscoll Health System, Texas Children’s Health, March of Dimes, CHRISTUS Health, Texas Hospital Association, St. David’s Foundation, TMF Health Quality Institute

Parking: Park in the AT&T Center garage, which can be accessed on the North side of the building, on 20th Street. Bring your parking ticket in with you and we will provide a second parking ticket that will pay for your day parking.

The morning portion of the first day of the conference will be live-streamed for those interested in viewing remotely. The morning session will include presentations on Zika screening and care coordination, the current epidemiology of Zika, Zika-related newborn outcomes, and current CDC guidelines for testing and management of pregnant women at risk.

The Texas Collaborative for Healthy Mothers and Babies (TCHMB) is facilitating a two-day conference on January 22 – 23, 2018 at the AT&T Conference Center in Austin, Texas. The conference is titled: “Obstetrical and Neonatal Care Coordination Related to Infectious Diseases in Pregnancy."

Top clinical and social services experts from around the state will identify gaps, best practices, and opportunities within the current system. This working meeting will help formulate a committee opinion, which will include recommendations for strategies and processes to improve the health and experience of care for mothers and babies. These strategies will be shared both locally and nationally. Download the agenda.

Registration for this event is free and includes breakfast, lunch and refreshments for both days. Each participant will be responsible for their own travel expenses, with a limited number of discounted hotel rooms at the state rate reserved at the AT&T Center.

Registration is limited and space is expected to fill quickly.

We look forward to your participation at this exciting event as we identify ways to improve the care and health outcomes for mothers and babies in Texas.

If you have any questions, please contact Susan Onion, Event Planner, either by e-mail sonion@utsystem.edu or cell phone (512) 636-2835.

*Registration Link: https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/CareCoordinationConference

AT&T Conference Center hotel room link: https://aws.passkey.com/e/49432530

*Very few spots remain for this event and your registration is not confirmed until you receive your registration confirmation e-mail.

CME – CNE Information

Texas Children’s Hospital is accredited by Texas Medical Association to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Texas Children’s Hospital designates this live activity for a maximum of 14.75 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)TM. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

This Continuing Nursing Education Activity awards 14.75 contact hours for registered nurses.

Texas Children’s Hospital is an approved provider of continuing nursing education by the Texas Nurses Association – Approver, an accredited approver with distinction by the American Nurses Credentialing Center’s Commission on Accreditation.

Participants must attend either one complete day or both days to apply for credit.